What’s the best way to exchange health information for our country?

I’ve been asked to speak about this twice this week: first to Caribbean region stakeholders tomorrow, then to decision makers in the EU next week.

Both times, I’ll start with the same story.

In the 1970s, mainframes arrived in factories. Manufacturers faced a coordination problem: thousands of parts, hundreds of workers, dozens of stations. They needed to ensure raw materials were available for production, keep inventory low, and plan deliveries.

Their solution was a centralized software called Materials Requirements Planning (MRP). It would collect data from thousands of workers about what to do next, when, and how. These systems cost tens of millions of dollars to design and deploy.

They never really worked.

If even one worker provided wrong information, or didn’t receive instructions at the right time, or had a machine problem, the system’s state diverged from reality.

Workers learned to ignore the computer. They developed informal ways to exchange data: paper notes, phone calls, and shouting across the floor.

Sounds familiar?

We’ve built Health Information Exchanges, centralized registries, national databases. And when they don’t have what we need? Fax machines. Phone calls. Asking the patient for the same information for the hundredth time.

Do you have any allergies? What medications are you on? Have you had any surgeries?

The moment there’s a chance the EHR is incomplete, the whole system falls apart. We revert to informal methods, just like those factory workers in 1970.

I’ve been working on this problem for 8 years.

In 2018, I tried solving it with blockchain and IPFS (I know, I know). I didn’t figure it out, but the problem I was trying to solve was the same: move patient records reliably.

We’ve come a long way since then. We’ve helped governments implement health data exchange in Andhra Pradesh, India and recently in Catalonia for 8 million patients.

But this is still the same problem we’re trying to solve. And Toyota figured it out 50 years ago.

The Kanban system

Toyota couldn’t afford to play this game. They lacked the capital for MRP systems and mainframe computers. So they simplified the problem instead.

Their philosophy: “We have a complicated problem, so we’d better simplify it so we can develop a simple solution.”

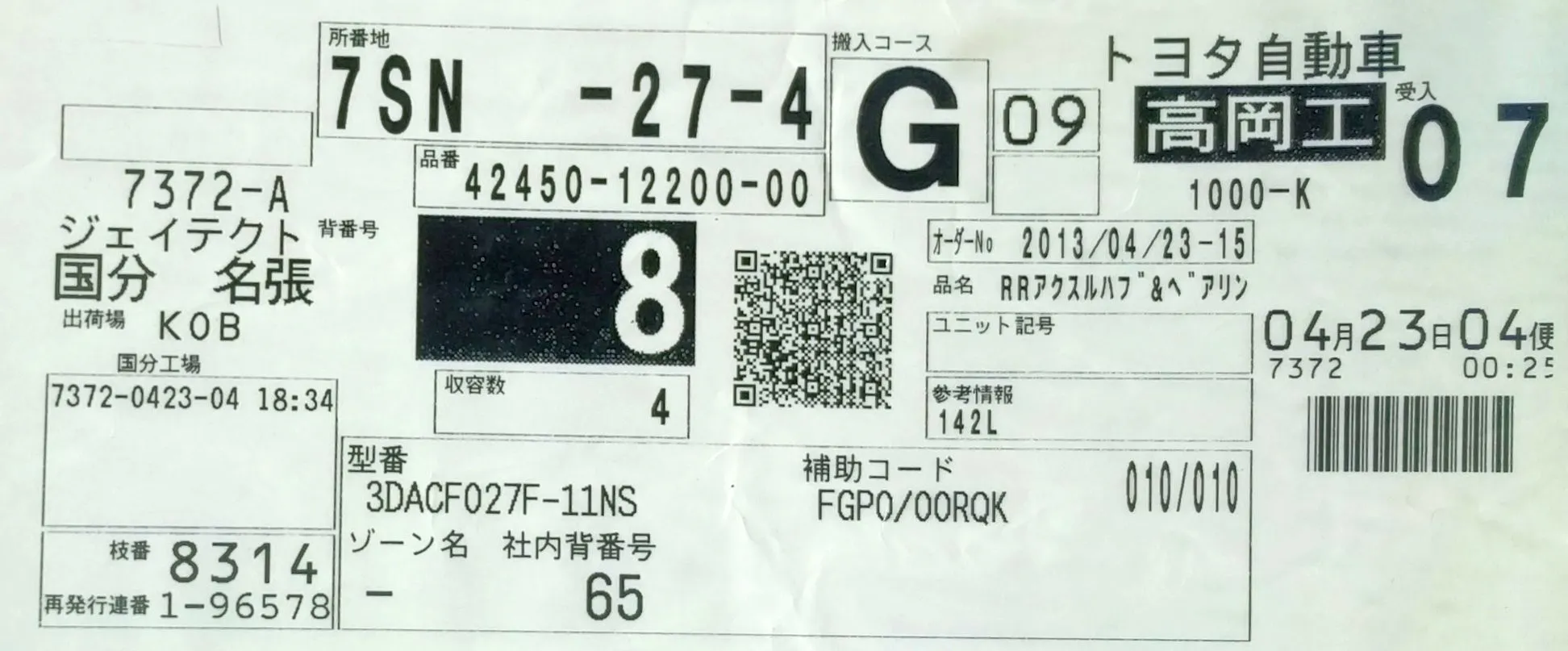

Instead of a centralized system that collected and dispensed information, Toyota decided that all information should travel with the product. Visible to everyone who needed it. In a standard, immediately recognizable format.

This was the Kanban system.

A single card attached to each product. It contained the part number, quantity, where it shipped from, where it was going, what route to take, order number, date and time. Everything a worker needed to know. And it always traveled with the product, through the plant and across warehouses.

No checking a central system. No waiting for instructions. Pick up the product, read the card, do the work. (There’s a lot more detail on how these cards evolved, but you get the idea.)

This actually worked. Workers had to update the card before moving the product to the next station. It was part of the workflow, not an afterthought. The information became the product’s shadow: always attached, always current.

And it cost almost nothing. Just cards and ink. Meanwhile, the “sophisticated” MRP solution was burning tens of millions on centralized systems that workers learned to ignore.

Health Information Exchanges

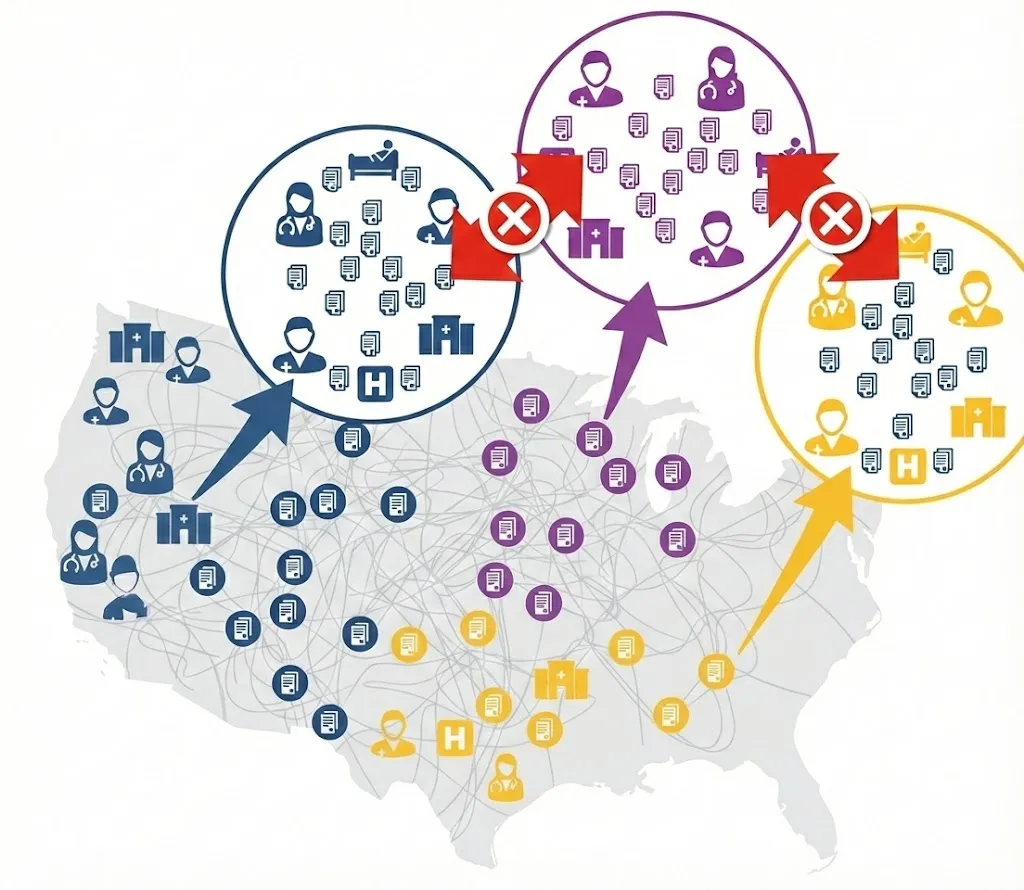

Back to healthcare. What’s our version of the expensive centralized system that doesn’t quite work?

Health Information Exchanges. National registries. Network-to-network data sharing agreements. All operating behind the patient’s back.

The idea sounds reasonable: connect all the hospitals and clinics to a central network so they can share patient data with each other. The patient doesn’t have to do anything. Data just flows.

But here’s the thing about networks that operate without the patient: you have to trust everyone on the network.

When patients aren’t involved, someone has to verify that every actor requesting data is legitimate. This is expensive and imperfect. Just this month, Epic and several health systems sued Health Gorilla for allegedly running a “syndicate” that used fake provider credentials to access nearly 300,000 patient records and sell them to mass tort lawyers. The data was requested under the guise of “treatment” but was never used for patient care.

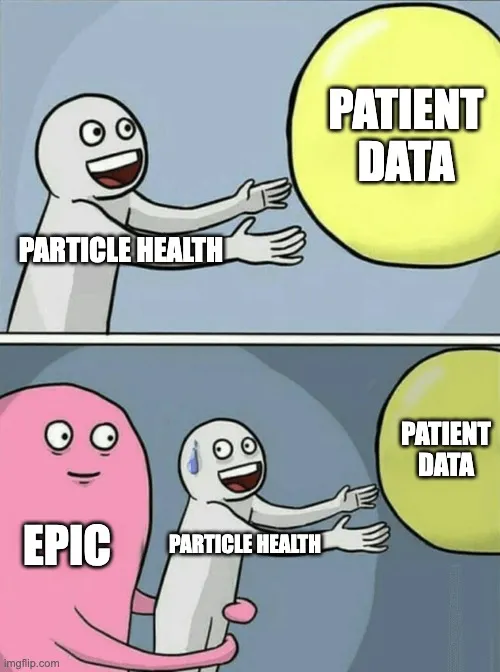

Meanwhile, Particle Health is suing Epic for blocking its access to data, claiming Epic uses its dominant position to suppress competitors. Epic says Particle was misusing data. Particle says Epic is monopolistic.

This is what happens when you build a system where the patient isn’t involved: everyone argues about who the “good actors” are.

You need middlemen to verify legitimacy. And every middleman has a cost. Network operators. Integration vendors. Certification fees. Compliance audits. Someone has to pay for all this infrastructure.

Want to connect to CommonWell, one of the major health information networks? That’s $25,500/year minimum. If your organization makes over $3 billion in health IT revenue, it’s $1.5 million per year. Plus a $10,000 onboarding fee. And expect at least 8 weeks to integrate.

And after all that, you still don’t get all the data.

In the US alone, you have CommonWell, Carequality, eHealth Exchange, and dozens of regional HIEs. Not everyone is on the same network. Programs like TEFCA are trying to unify them, but even there, some networks are more forthcoming than others.

These are our MRP systems. Expensive. Complicated. Built on the assumption that a centralized solution is the only way. And just like those factory workers in the 1970s, healthcare workers learn to work around them. They pick up the phone. They send a fax. They ask the patient the same questions again.

But what if we took Toyota’s approach instead?

Healthcare’s Kanban: Personal Health Records

What if the data just traveled with the patient?

This isn’t a hypothetical. In the US, regulations have already made this possible. The ONC’s Cures Act Final Rule and CMS-9115 require healthcare organizations to expose patient data in a computable format (FHIR R4). They have to publish their API endpoints publicly, and make the process of building apps on their data obstruction-free.

The result: patients can log into their hospital’s portal, authorize an app, and pull their records. Any app. Not just the hospital’s official app. A third-party app the patient chooses.

I built an app on Epic’s live patient portal this month. On a livestream. In 3 hours. That’s how accessible this has become.

The patient logs in with their existing credentials. The app pulls their records. The patient takes those records wherever they go. To another hospital. To their doctor. To an AI assistant. Wherever.

Data travels with the patient. The Kanban principle, applied to healthcare.

And it’s essentially free. No $25,500/year network membership. No 8-week integration cycles. No middlemen arguing about who’s a “good actor.” The patient is the actor. The patient decides who gets their data.

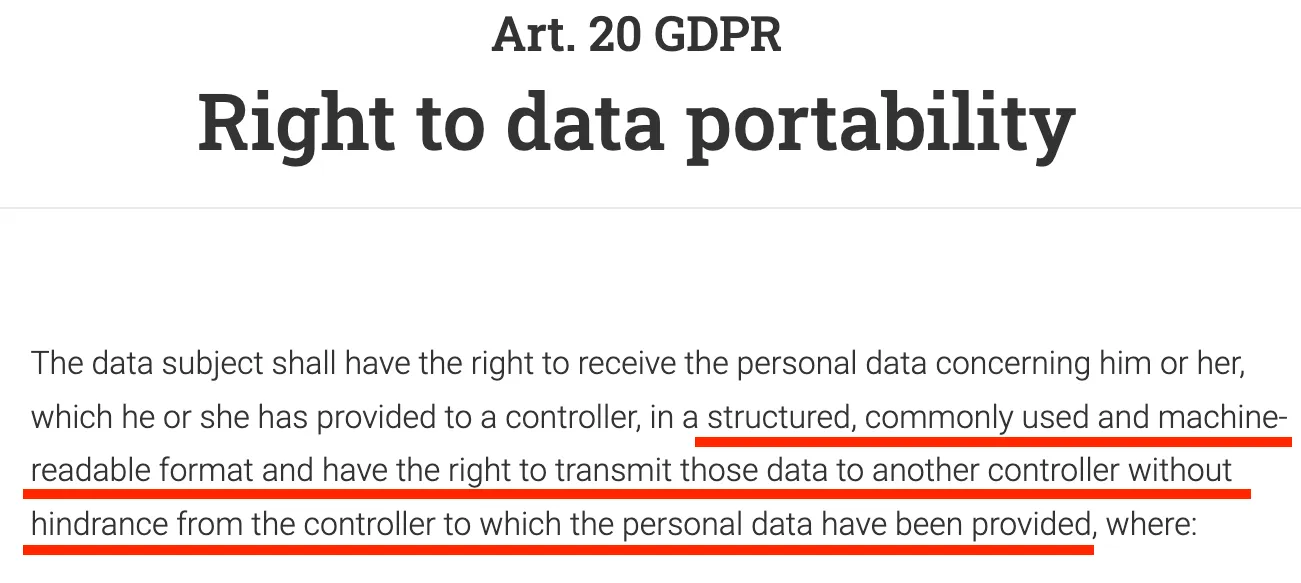

The funny thing is: the laws have supported this for decades. HIPAA has given patients the right to their records since 1996. GDPR’s Article 20 (2018) goes further, requiring data in a “structured, commonly used and machine-readable format.”

These rights existed on paper. The information blocking regulations just added teeth: it has to be programmatically accessible, via FHIR R4 endpoints, and organizations can’t obstruct the process.

Why We’re Not There Yet

So if the laws are there and the technology exists, why isn’t everyone using PHRs already?

Right now, patients have to log into a different portal for every hospital, every insurer, every lab. Different usernames. Different passwords. Different apps. The average patient has visited multiple healthcare providers over their lifetime. That’s multiple portals, multiple logins, multiple places where your data is scattered.

PHR apps are supposed to solve this: one app, many sources. But we’re not there yet.

The root cause? Identity. Each hospital verified your identity separately when you registered. Each gave you separate login credentials. There’s no universal way to say “I’m the same person who visited Hospital A, Clinic B, and Lab C.” So you’re stuck logging into each one individually.

But this is being solved.

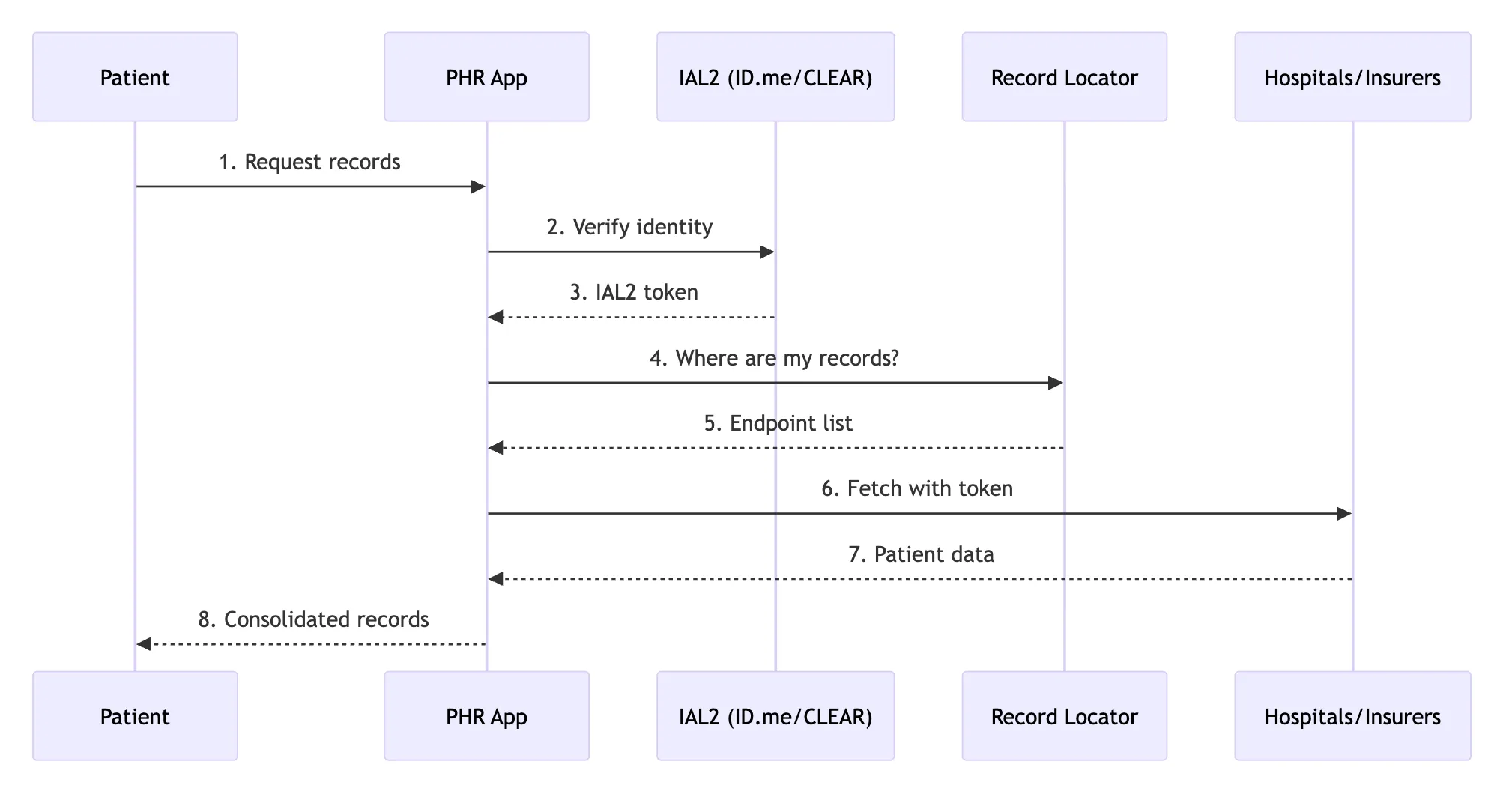

I recently saw a demo of TEFCA’s Individual Access Services (IAS) by Flexpa in action. I couldn’t believe this was possible today.

Here’s how it works: identity providers like ID.me and CLEAR verify who you are using government credentials or video proofing. They issue an IAL2 (Identity Assurance Level 2) token. Your PHR app uses this token to request records from any FHIR endpoint. The hospitals don’t need to trust your app directly. They just need to verify the IAL2 token, which anyone can do by verifying the public key of the identity provider.

One identity verification. Access to all your records.

There are quirks, of course.

TEFCA still maintains a Record Locator Service to track where patients have received care, so PHRs know which endpoints to query. Epic, being Epic, doesn’t give data directly after IAL2 verification. They require patients to log into MyChart again (for security, they say). And most data coming through other networks today is in CCDA format, not FHIR.

But the potential is there.

Technologies like IAL2 and UDAP could eliminate the need for a central record locator entirely. All FHIR endpoints are required to be public. A PHR could maintain a directory of these endpoints and poll them periodically after a patient provides an IAL2 token.

No central infrastructure required.

Or maybe we decide two services are essential: a government-run Record Locator Service so PHRs know where to look, and a government-maintained list of approved IAL2 providers. Either way, this centralization is far leaner than whatever HIEs were doing with data middlemen.

But what about patients who don’t engage? What about those who don’t know how to use a smartphone, or simply don’t care enough to pull their own records?

Here’s the twist: hospitals can act like PHRs too.

If a hospital can verify a patient’s identity via IAL2 (face verification, government ID), they can pull that patient’s records from anywhere. Instead of backend networks exchanging data behind the scenes, the data is unlocked by the patient’s face. Right there at the registration desk.

The patient is still the “key” to their own data. They just don’t always have to be the one turning it.

The Promise

Here’s what excites me most: this scales globally.

You don’t need country-wide bridges. You don’t need international health data agreements. You don’t need governments negotiating interoperability treaties.

You just need policy forcing all Health IT vendors to open up their data to their own patients, programmatically. That’s it. The internet becomes the health information network.

A patient from the US goes on medical tourism to a hospital in Singapore. They verify their identity. The hospital (acting as a PHR) pulls their records from their providers back home. No bilateral data sharing agreements. No middleware. Just a recognized IAL2 provider (there will probably be a dozen of these around the world max), publicly available directory of endpoints, and a patient who consents.

The patient is the integration layer.

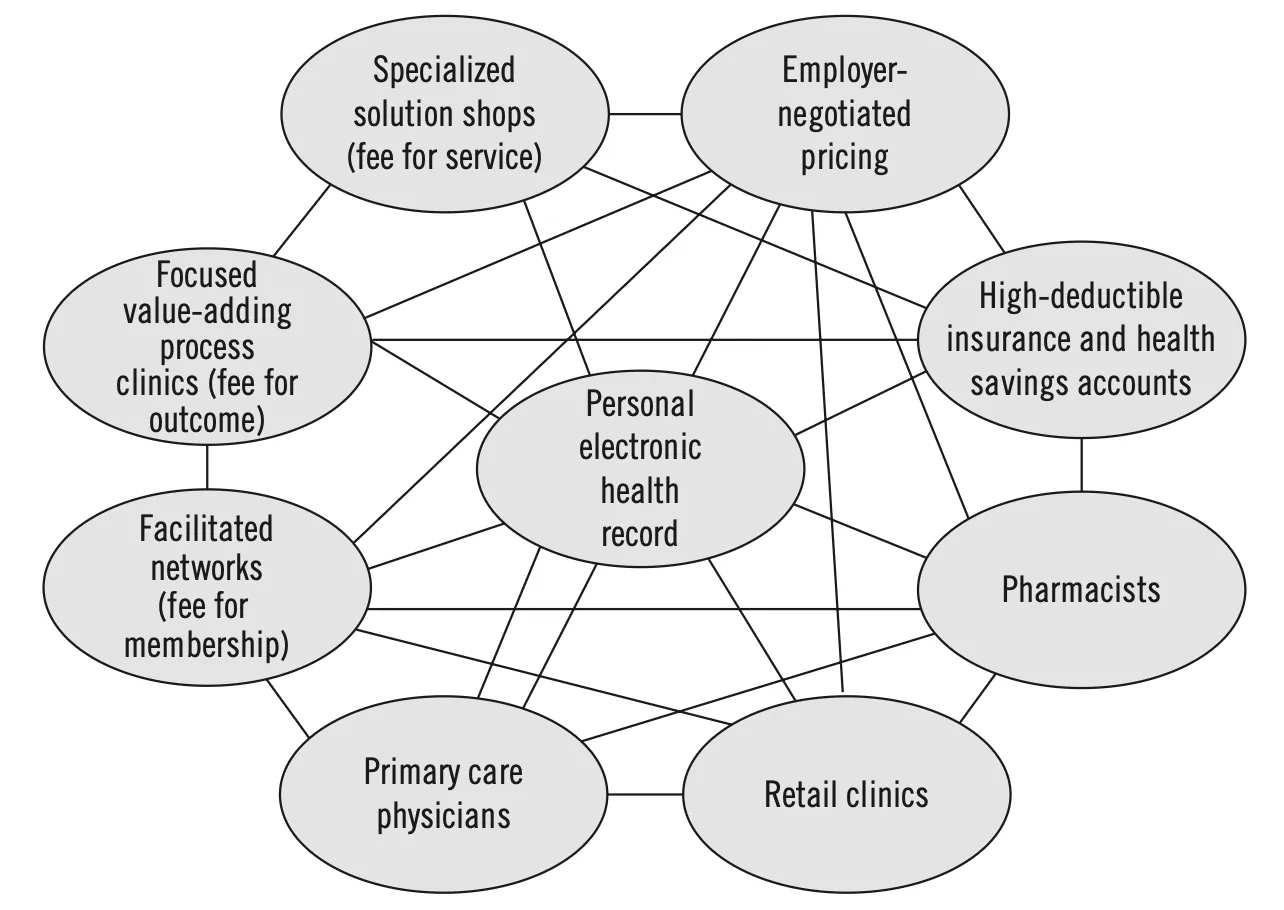

(above image and Toyota’s story from The Innovator’s Prescription - highly recommend read)

And think about what this enables. AI assistants that actually know your complete medical history. Research studies where patients can contribute their data with a single consent. Second opinions from specialists anywhere in the world, with full context.

ChatGPT connecting to your health records is just the beginning. The concept is right. Josh Mandel’s demo shows both the potential and the gaps. We have a long way to go on execution.

The architecture is sound. Toyota figured it out 50 years ago: data should travel with the thing it describes.

What I’m working on

I’m still exploring what this looks like in practice. Right now, I’m mapping how real US Personal Health Record exports look across hospitals. You’d be surprised how much variation there is, even in “standard” formats.

I asked for help with this last time and received great responses from many of you working in health IT. A few vendors offered anonymized datasets, which I appreciate. But for this study, I specifically need individual patients who can consent to share their own records. If you’ve received care or have health insurance in the US and are willing to export your records, I’d love to include you. $100 gift card as a thank you. Fill out this form if you’re interested.

Overall, PHRs aren’t just another way to keep patients engaged. They’re a completely new approach to interoperability. One that aligns incentives, reduces costs, and puts patients in control.

If you’re working on this problem, I’d love to hear your thoughts. If you want to schedule a conversation, book a call here.

If you’re building with healthcare data and want to go deeper, join our free webinar Build your first FHIR App next week.

And if you want something more comprehensive, our FHIR Bootcamp also starts next week. We’re running 30% off this week only.